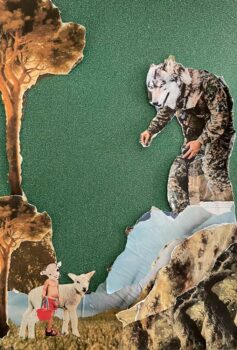

The Wolf and little Lamb

Annelie van Steenbergen, text and illustrations

‘Grandma, you would do so too, if you were alone in the wild and hungry!’

my eight-year-old granddaughter said sympathetically. She hung out on the couch with her nephew, each with a phone in their hands, playing a computer game together. In addition to defending themselves against enemy monsters, they tried to survive in this cube-shaped virtual world by mining resources for building and foraging for food. They obtained this food by growing grain and vegetables or by slaughtering animals, so that they would be supplied with meat and leather and wool — something like that.

I still don’t understand the good thing about it. At least my two grandchildren were, each on their own screen, encountered on a meadow with sheep, which they wanted to kill for charity.

‘Killing them?’ I cried in horror. ‘Isn’t that cruel?’

My granddaughter’s sober response not only made me laugh, but also made me think. She did not ask ‘what would you do?’, but stated ‘you would do that too’!

My granddaughter put her finger on the sore spot with her comment. In other words, she said that I, as a human and grandmother, am also a predator. And that was something to swallow.

We like to believe in the Golden Rule: what you don’t want done to you, don’t do it to someone else. Apparently that rule depends on the circumstances. When one’s own life is at stake, it is done with good intentions.

Fairy tales, myths and fables are eminently suitable for investigating these kinds of life questions about Good and Evil due to their universal character.

For example, in this particular case, the fable of the Wolf and the Lamb[1]. The great fable writer Aesop, who lived from about 620-about 560 BCE, used this fable to show that the evil and the wicked and the greedy always find something to extort money from the innocent.

At least that’s the moral. To reach this conclusion, he deployed a wolf, who makes up all kinds of arguments to outwit an innocent lamb on the bank of a stream. The lamb doesn’t stand a chance, and the wolf is the main culprit.

My granddaughter’s observation puts this fable in a different light.

‘I am that wolf myself!’

As a wolf, I was a bit blown away by the morality of that fable, which the poet has pasted on. It is an insult, a denial of my true nature.

Later, Jean de La Fontaine (1621–1695) put the story in rhyme[2] and adapted the moral, namely that the strongest is unfortunately always right. Nevertheless, as a wolf, I remain the culprit.

Why did those storytellers choose me to spread their pedantic tales? Why not a raccoon or a hedgehog, or, when we’re on the subject, just plain and simple, a human? They don’t all come up with their manipulative display of power. And it’s not just about sheep…

Compared to that, we wolves aren’t that bad. We too are loving parents, we have thriving family lives, we are excellent leaders, we have effective means of communication, we are courageous and adventurous, and we take good care of our sick and infirm. In addition, we keep track of the game stock, we decimate the surplus of wild boars and only when they are handed to us on a silver platter do we occasionally grab a sheep or a tender lamb. Who can blame us for that.

You can imagine. Such an inexperienced lamb, straying from the flock. Her mother and aunts are a little further away with her good half-brothers and sisters. Her mother warned her every morning, shaking her curls and licking her snout: stay with us, don’t lose sight of us, don’t go with strangers, think of the big bad wolf.

And so far she has. But she is thirsty, and the clear water of the stream glistens invitingly. What harm could it do, to take a sip from there, instead of from the soiled trough the farmer has set up for that purpose. The farmer, who has failed to put up a fence with electricity on it, because the meadow is already surrounded by water, except at the dam. There is a beautiful wooden fence, which the lambs cannot crawl under, one that we wolves can easily jump over.

Little lamb was an adventurous animal and, moreover, she talked like a waterfall and spoke against me, very politely. She shouldn’t have done that. She should have run away, bleating loudly, towards the herd, then I might have taken another lamb, or maybe I would have turned around. Actually, it was the fault of the lamb, not of me, the wolf, if you think about it correctly.

It is hard to love a total stranger — and in the imagination of the people we are bloodthirsty monsters. The people, who themselves unscrupulously serve their domesticated house dog lamb, freshly steamed, with vegetables from the garden, are scared as hell of us. As if we have little boys on the menu every day.

Do you know how many human victims my kind has killed in the past fifty years? Nine. Nine[3]! Would you believe that, eh, so little?! And, if I may ask, how many human victims does your species make? We always have to pay for your faults. I’m getting a little fed up with that. I think, one day, I’ll put an end to this humiliation and your abusing us — and eat you all in one bite. Just kidding, don’t worry. My fantasy took me in the moment. That’s because, because of my granddaughter’s comment, I crawled into the skin of the wolf unnoticed.

First, let’s see what Aesop’s fable tells us about it. It is a fable about a wolf and a lamb, who are both thirsty and drink water on the bank of a river. The wolf upstream and the lamb downstream.

In the translation of Jean De la Fontaine’s rhymed version, the lamb is urinating in the river, it is not clear whether “pee” means splashing or urinating. It would have been nice if De la Fontaine had let the lamb pee in the river to sharpen the situation. In the original, however, it says.

‘Un Agneau se désaltérait dans le courant d’une onde pure,

that is, he has only quenched his thirst in the clear stream.’

In any case, the wolf speaks to the lamb in sharp terms:

‘Crook’, he growls, ‘why do you soil the water I want to drink?’

The lamb immediately apologizes. ‘Excuse me, my dear lord’, he says, according to Aesop.

‘With respect, but the water comes from you to me anyway.’

The wolf does not take that, such a brash lamb who dares to contradict him.

‘Aren’t you ashamed to curse me?’

Aesop does not mention in the short fable if the hairs on the neck of the wolf stand on end, that is superfluous, we can safely assume that.

Little lamb is not afraid. It doesn’t flinch and repeats:

‘My dear lord, with all due respect.’

The wolf remembers that the biggest insults are accompanied by the remark ‘with all due respect’, it is an empty phrase. He has to come up with something else to make the lamb back off.

‘Didn’t your father do the same to me six months ago?’

The lamb is unstoppable and answers: ‘I wasn’t born then.’

He doesn’t even stick his tongue out at me, the wolf thinks.

‘You ate my grass,’ he growls. ‘How is that possible’, laughs little lamb, showing its mouth, ‘because I don’t have any teeth yet.’

Now little lamb is crossing the line, being laughed at, thinks the wolf. In that case, little lamb has to take care for himself. He has done his best.

Enraged at the insult, done to him, he hisses:

‘You look just like your father and you must die for his crime.’

Aesop writes: ‘The wolf then took the lamb and ate it.’

Jean De la Fontaine takes a slightly different approach to the fable. First, the wolf has an empty stomach with him, for “sober, fasted”, and little lamb humbles himself and begs the wolf to see that it was impossible for him to make the water cloudy, because the water is flowing downwards. Whatever the lamb says to prove his innocence, the hungry wolf doesn’t care. He puts the blame on the weak shoulders of the innocent lamb, the blame of the whole flock, the shepherds and even of the dogs.

The story demands a good lesson in the end. –

Even without any form of process

Has Grimbeard devoured one, two, three, devoured the poor sheep.

And then the moral follows:

Alas, this is how it goes in the sublunary world:

The strongest is always right!

Where in Aesop the wolf is compared to angry, bad, greedy people, our predator in De la Fontaine is in search of food and makes use of its power and strength, as hedgehogs eat the worms and dragonflies a fly. Here it is rather unavoidable, unfortunately.

Because, to speak to my granddaughter, what would I have done if I had been a wolf and starving?

The problem in this fable is not so much that the wolf takes the lamb, which is to be expected. The problem is that he makes up all kinds of arguments to justify his deed. He makes the lamb mistakenly think there is a way out.

Animals in fables embody the different sides of the spectrum of Good and Evil, of wisdom and stupidity, and provide food for thought. The human adage that everyone is equal and no one has the freedom to do something to another, to harm another in his or her life, is questioned in fables and calls for a conscious vision of good and evil in our cultures and societies, also at national level and global level.

The Wolf in this fable stands for Man, and we expect a person to have empathy and to apply the Golden Rule. We assume that he thinks ethically and makes the right decisions. If that expectation is not met, we call him angry and evil and greedy…

So it’s a matter of perspective and interpretation, and that’s what makes the fables so fascinating. We ask ourselves how we interact with each other, within our place in society and within our possibilities. Are we the good guy or the bad guy? When and in what circumstances?

Anyway, Lambs need to be careful and stay away from that Big Bad Wolf. And I teach my granddaughter just to be sure she shouldn’t get involved with bad, greedy, and malicious people.

Notes

[1] (2016) Het leven en de fabels van Esopus. Teksteditie met inleiding, hertaling en commentaar door Hans Rijns en Willem van Bentum. Hilversum: Verloren, pp. 163-165.

[2] Jean de La Fontaine (nagevolgd door J.J.L. ten Kate) (1875, ?, 1e druk)- De fabelen van La Fontaine. Geïllustreerd met platen en vignetten door Gustave Doré. Fabel X, Eerste boek. Amsterdam: Gebroeders Binger, pp. 31-35.

[3] Elli H. Radinger (2022). De wijsheid van wolven. Zesde druk. Amsterdam: Bruna Uitgevers B.V., p. 223