The Rat and the Frog

Text and Illustrations by Annelie van Steenbergen

Translation by Greg Suffanti

You don’t expect rats to go on a pilgrimage, with knapsack and pilgrim’s staff, on the way to a holy goal? And yet, the first sentence of Aesop’s third fable is: “One day the rat went on a pilgrimage.”

Pilgrims traditionally have a religious purpose. In classical antiquity, the time in which the fabulist Aesop lived, believers travelled to temples or oracles or to other places associated with the worshipping of gods. And although many people, young and old, nowadays set out for other kinds of purposes, most pilgrims still walk or cycle so that they can think about the meaning of their lives, to look for solutions to life’s questions, to gain insights, perhaps even liberation and a new, more satisfying existence. How can we reconcile these noble goals with the ambitions of a rat?

Going on a pilgrimage is no small task. There are all kinds of dangers associated with this kind of undertaking. Apart from the fatigue, the blisters and broken feet, hunger and thirst, finding a place to sleep, the traveller may be confronted with scams, collisions or other accidents, robbery, rape, etc … The question is whether you will achieve the goal, whether you can persevere, through all kinds of weather and setbacks? Is what rat does something like this?

It was certainly not a brown rat that Aesop was referring to in this fable about The Rat and the Frog.[1] The first obstacle the rat encounters is a river. A brown rat could have easily crossed by swimming, it could have even stayed in the water for up to three days at a time. He certainly wouldn’t have let himself be fooled by some mean little frog. So it must have been a black rat, that’s for sure.

Why does it matter, you may say, brown or black, a rat is a rat? However, that is not the case. Although a black rat has a longer tail than a brown one, overall it is a lot smaller and also weaker. If you were to put a black rat in a cage together with a brown one, the black one would be killed and summarily eaten by the brown one without any qualms whatsoever. Just read Nils Holgersson’s famous story: In it, a black rat colony is unmercifully attacked by a brown invasion. You have to be careful with black rats. Perhaps through experience our main character had become a bit timid, more gentle, perhaps more polite than an average brown rat? In any case, she had to have had high and spiritual aspirations, otherwise she would not go on a pilgrimage in the first place.

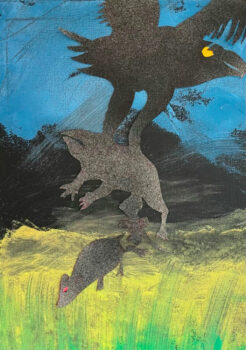

What is this ultra-short fable by Aesop about? The rat is on a pilgrimage and comes to the bank of a river in the evening. She then asks a nearby frog to help her get to the other side. The frog sees his chance, ties one of her legs to his own, and then swims with her in tow to the middle of the river and stops there to let her drown. After that, he plans to eat her later at his leisure. While she struggles for her life, a kite suddenly swoops down and grabs them both and takes them away for her own meal. End of story.

Except that there is of course another moral lesson: “A person who thinks evil is goodness will be paid for with the evil he or she thinks.” Or, as is written at the introduction of the fable: “It teaches us this: evil thoughts and actions of one who thinks evil of another who thinks not evil, but is good in faith, will not go unavenged.’

Jean de La Fontaine (1621-1695) made a rhymed version of this fable about two thousand years later, in The Frog and the Rat.[2] According to de la Fontaine, the moral is simple: “Whoever digs a hole for someone else is often the first to fall into it.” He borrows this proverb from Cats, ‘or who said this’ and he considers this fable a good example of this deeper meaning about life. Instead of Aesop’s rat, a pilgrim with lofty intentions, who has to overcome obstacles while walking and talking about the stirrings of her soul, he introduces a prosperous, obscenely large rodent, one:

“Who lived according to the flesh:

Never go hungry or fast!

Snacking, snuggling, always eat something!”

This enormous rat behaves like a smug brown rat, sure of himself, not afraid of danger. He strolls leisurely along the shore of a pond where he encounters a frog who immediately realizes what kind of meat he could have in store for himself and tries to persuade the rat to come and have a meal with him.

“Come dine with me!

And be my guest.”

Even though our gourmet immediately accepts this tempting proposal, the frog makes a whole show of it and begins a page-long list, in rhyme of course, detailing all the delights that a visit to his El Dorado entails for the rat, even of miracles and

“Of the strange skills,

From love to music,

Of the laws and morals

Of this Water Republic.”

The interesting thing is that here we refer back in passing to our pilgrim from Aesop’s fable, because the frog shows him the joys of a pilgrimage. Namely, reaching a holy place, a paradise, with miracles, encounters with other cultures, a journey to a place of revelation, enlightenment. The frog even points out to him that by accepting the invitation he will benefit from it later, just like the pilgrims who can recount all about their adventures once back at home:

The interesting thing is that here we refer back in passing to our pilgrim from Aesop’s fable, because the frog shows him the joys of a pilgrimage. Namely, reaching a holy place, a paradise, with miracles, encounters with other cultures, a journey to a place of revelation, enlightenment. The frog even points out to him that by accepting the invitation he will benefit from it later, just like the pilgrims who can recount all about their adventures once back at home:

“Rat would be telling in his old age

his children’s children many times

the stories from this Paradise.”

The rat is delighted by this prospect, but he has one objection: he can swim a bit, but he can’t really do it without help. The frog knows exactly what to do, he says, finding a strip of cloth with which he ties one of the rat’s legs to his own, and then they go into the water together. Like Aesop, the frog stops in the middle of the water and tries to pull the rat underwater in order to drown him.

“So outrageous, horribly bad,

He offended good faith and international law.”

The frog is looking forward to the taste of his anticipated feast. He can already hear the bones cracking, but he has ignored the rat’s urge to survive. With his last bit of strength, fearful and trembling, ‘already more dead than alive’, the rat calls on the gods for help. And then a fearsome fight breaks out, which attracts the attention of a Vulture flying past, drawn by their endless splashing about. No noble kite in this case. The bird of prey swoops down, extends its claws and fishes the intertwined pair out of the water. Flapping his wings, he then disappears into the distance with his loot.

“Well, the vulture was quite at peace,

as he had a double evening meal

with both meat and fish”.

De la Fontaine concludes, by observing that although trickery often triumphs, evil often punishes evil.

“Many times it will be betrayal

turn upon the traitor’s skull.”

What do the two writers want to convey to us? In one case, a well-intentioned rat with high expectations is lured into a trap by a seemingly helpful fellow creature. For the reader, in addition to the explicit warning not to harbour bad thoughts, it is also advice to be on your guard and not to fall for anything.

What exactly does that advice amount to? To not be naive and blindly trust everyone? That you can’t just rely on someone else and need to arrange as much as possible yourself? If so, you could never ask for help without risking your own life. While on pilgrimage routes strangers are generally very nice to the wandering pilgrims. They are willing to help if needed and are happy to give advice to lonely walkers and cyclists. Or is it an indication that the path of life simply involves risks and is full of dangers that you have to face and that sometimes, if it is necessary to get where you want to go, you have to take those risks?

Why has De La Fontaine turned the pilgrim into a well-off rat, who has more than enough of everything and wants more and more? Is that a sign of his times, the Seventeenth century? Was it meant mockingly? Both a ‘bean gets his money’s worth’ and a ‘he who digs a hole for someone else’?

In Aesop, the reader’s sympathy lies with the rat, the gullible victim of a sneaky ruse. In De La Fontaine there are two culprits, one due to his lazy existence, the other due to his criminal act. Both misbehave in a sense, the rat through unlimited consumerism and the frog through a lack of ethics, you could say. The moral disapproval concerns both.

What could a reader today learn from these old fables, apart from the warning that anyone who thinks evil of good will one day get a taste of their own medicine? It’s worth thinking about that. You don’t necessarily have to take out your walking shoes or bicycle for this. Instead, you can also take a journey in your mind without the danger of falling prey to malice. You can try to transfer the fables to this present time and think about the position we find ourselves in. How would we ourselves respond in these circumstances, on the way to our much-desired holy goal? In other words: how to live?

Fables often have moralistic features, and isn’t that precisely the challenging thing about fables, whether they are by Aesop, by De La Fontaine or something you made up yourself?

Notes

[1] Het leven en de fabels van Esopus (2016). Teksteditie met inleiding, hertaling en commentaar door Hans Rijns en Willem van Bentum. Hilversum: Verloren, p. 165.

[2] Jean de La Fontaine (nagevolgd door J.J.L. ten Kate) (1875?, 1e druk) De fabelen van La Fontaine. Geïllustreerd met platen en vignetten door Gustave Doré. Fabel X, Eerste boek. Amsterdam: Gebroeders Binger, pp. 220-223.