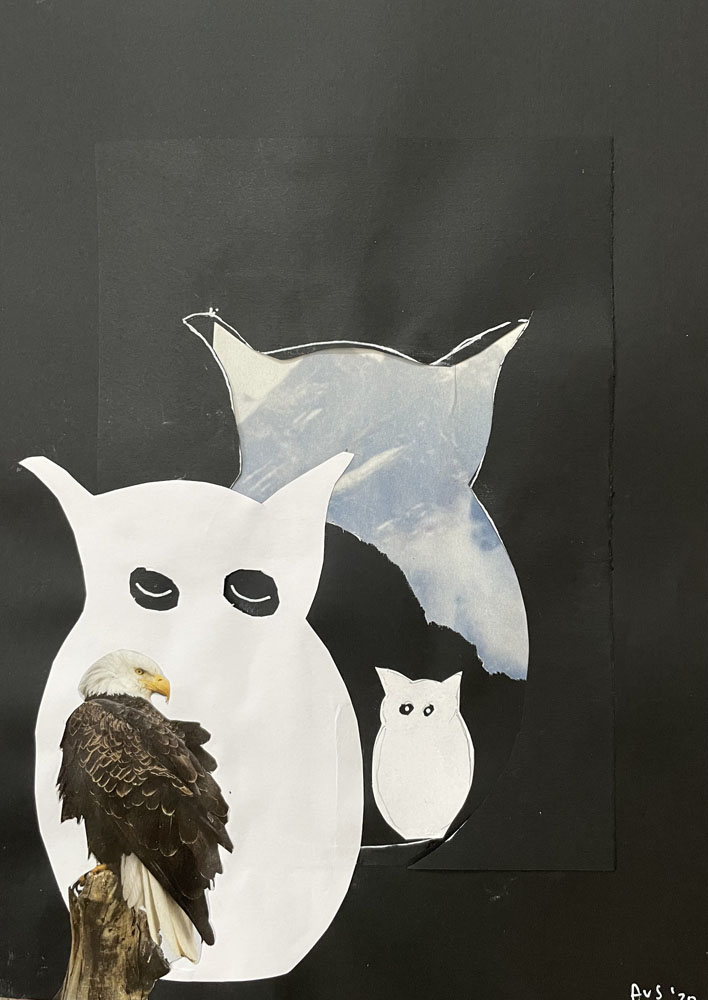

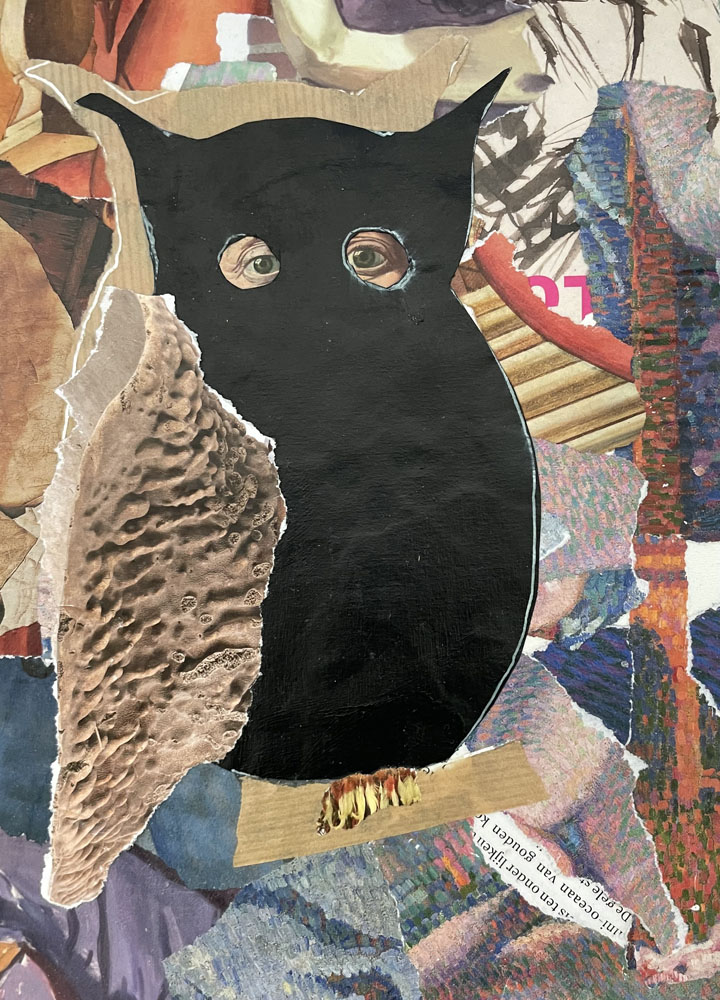

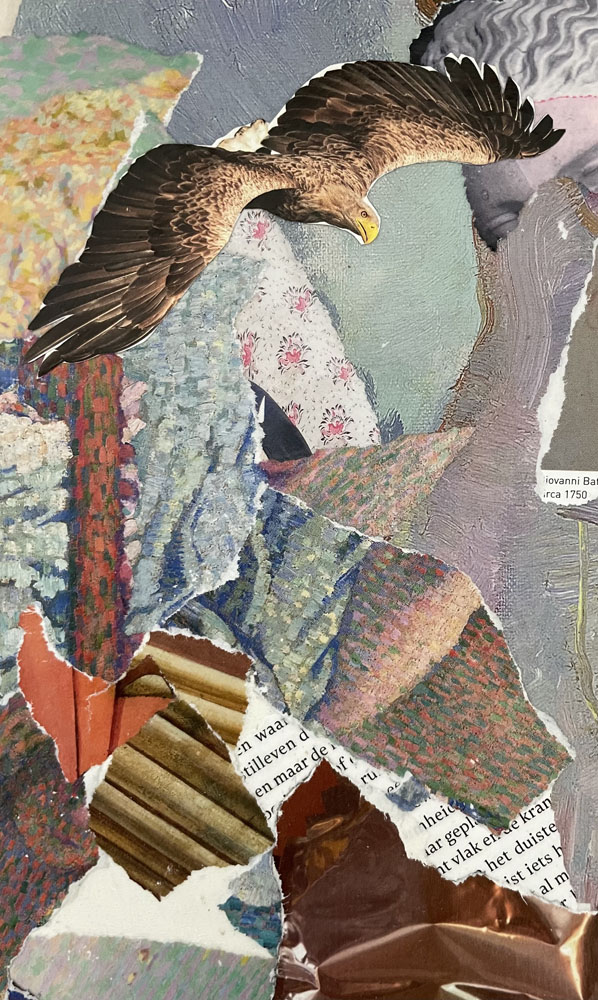

Text and Artwork by Annelie van Steenbergen ― translation by Greg Suffanti

As originally told by Jean de la Fontaine, The Eagle and the Night Owl, book V, fable XVIII[1]

At first she was surprised that this giant, this tyrant, actually cared about her. He sat down next to her, and after her initial astonishment passed, she composed herself and acted as if it were the most natural thing in the world that this being chose to sit by her. This great being deigned to perch next to her. He got straight to the point, and she liked that.

“How do I get food here?,”

was his first question.

“Spiritual or carnal?”

She allowed herself a small joke.

“Both,”

he replied.

That broke the ice. She told him where to acquire tasty snacks, where the best quality was, and how to get them. It was already evening and he couldn’t find his way in the dark. This was a piece of cake for her however, as she knew all the nooks and crannies, so she offered to get something for the both of them, moving silently through the labyrinth.

Not long afterwards they sat side by side, devouring their meals. The next evening he came back again, and so their friendship began.

Their relationship was based on mutual admiration, and on wonder. In almost all respects they were opposites, and they complimented each other through their individuality. He was the day, she was the night. He was the eye, she was the ear.

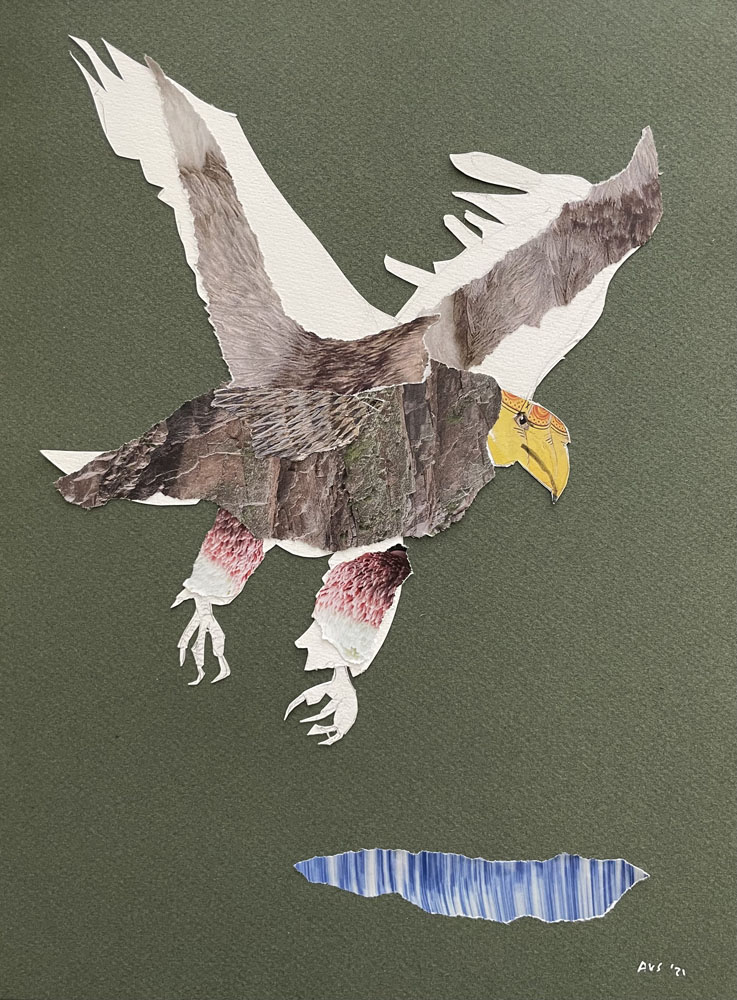

He was a striking figure with his characteristically white head and sharp gaze, and she was rather colorless, with a stocky body, and large, dark eyes and a round, flat face. When she looked at him, she needed to look up, as he was enormous, lightly built, yet extremely powerful, and this gave her the feeling she was shrinking. She listened in awe to his description of unknown distances and soaring heights, and his ability to face the sun without blinking. Undaunted and with a regal bearing, he’d spread his wings. Anyone who dealt with him, or saw him from afar, stared unashamedly until he was out of sight. No one could harm him, he was invincible.

You would expect a friendship between two such different characters to end badly. However, you’d be ignoring the fact that they had many similar interests, such as current restrictions on airspace, climate change, and habitat shrinkage. And of course they also had illustrious histories, both on a military and a spiritual level.

For example, he could endlessly elaborate on the Eagle god of the Sumerians or the double-headed Eagle of the Hittites. From time to time she would interrupt him, telling him about the support her family had given to the victory of the Greeks over the Persians, and later, to a successful campaign against the Carthaginians.

He tried to outshine her with the enormous prestige of being an eagle, a heraldic symbol of ancient Rome and numerous emperors, too many to mention. It was not easy to outdo him, so she told him of her own family’s coat of arms, Owl of Minerva, the symbol of knowledge, wisdom and acumen. Of course, he came up with God.

He was chosen by God, he claimed. He didn’t even call him his God, just God, as if he were her God as well. Their gods did have the same origin, and hers was derivative of his, he said. She thought Goddess, rather than God, but he said her god was born from the head of his god, and he was thus a personification of god, and she, his attendant.

She didn’t know how to respond to that statement. Eagle carried on as if he had a monopoly on truth, although Owl sometimes doubted if her Goddess was the one, and she thought he could be right, and so she bowed her head listening to his convincing arguments. Before this issue could drive a wedge into their precious friendship, Owl mumbled something about cultural differences and the right to freedom of belief, and then she went silent. She offered to steal some more edibles for them, and Eagle graciously accepted. A little later, they sat as happy comrades, nibbling and talking about this and that.

One of the less sensitive topics of conversation, and a theme in which they found each other, was their love for their children. And yes, also for what they termed their ‘brainchildren’…. Such as the genius of his housing or her way of dealing with waste problems. As different as they were, with their backgrounds and lifestyles, at the same time, they had much in common, which made their friendship blossom. They wholeheartedly agreed on raising their chicks to be worthy representatives of their species. They protected their young, fed them, raising them to be better copies of themselves. They taught them to hunt, to learn through trial and error, until they were ready to go out into the wide world on their own wings. In short, they wanted the best for their offspring and would kill for them.

As they talked they realized all of the dangers around them. Eagle worried about his young ones falling from great heights. Owl was concerned about robbery and murder. And she immediately also realized that her new friend was a risk.

“You wouldn’t hurt my little ones if you came across them, would you?,”

she asked, suddenly concerned.

“How can you think that? I would never do such a thing. Tell me how to recognize them, and I won’t harm them, I promise.”

She didn’t know what got into her. She began bragging about her little darlings, about how beautiful they were, how bright their eyes were, how they screeched when they were hungry, and how adorable they looked when they slept. They grew like weeds thanks to her good care and they developed into little gems, beautiful and handsome, easily recognizable from all the others, who were like wax figures.

Of course, in her more negative moods, she recognized they were like baby squirrels, with no fat on their bones under their abundant fluff, and not at all comparable to the chicks of her significantly larger friend. She sometimes wondered what made her produce these scoundrels. That, she consoled herself, was nature. What you bake yourself is tastiest.

Her friend understood her. He too was full with pride and described his children’s qualities in extraordinary detail.

“For sure I would never harm that which is so dear to you, as you have so described. Just as you promised you would never harm those so dear to me. We are friends for all time.”

It was natural that they thus agreed to spare each other’s offspring, while everyone else could count on their blood lust. After all, they had to survive. Each had to live according to their own nature. And so they sat in unison, night fell, she got something more to eat, and they were both very pleased.

However, the peace didn’t last. One dark evening Owl came home and discovered that her nest was empty! Not even a few bones or feathers or a bit of meat on a leg.

Eagle! It shot straight through her. How could she have trusted him?”

She should have known that such a robber and thief doesn’t change his tricks. She had left them unattended, counting on her friend’s trustworthiness in swearing not to harm her little ones, just as she had promised. What good is a promise if it is broken at the first opportunity? She had gone out for a moment and he had struck. She thought of her tiny fluffs, picked up by those sharp yellow claws, flying through the air, with their eyes still closed, screaming for her, their mother, in pain and terror. Had he already killed them in his iron grip? Let them loose onto the royal nest that was several meters wide? Had that brute torn her babies to pieces, feeding them to his own disfigured fledglings? Why hadn’t that miscreant chosen a pigeon or a duckling? Why did it have to be his best friend’s family? Wasn’t that particularly cruel? This marked the end of their friendship. What remained was the need for revenge.

She let out a hoarse wail:

“O Great Gods, punish the robber,

Who all of my children he did assail!”

The Fables of Jean de la Fontaine

The Eagle and the Night Owl is one of the many stories from French poet and fabulist Jean de la Fontaine (1621-1695). In addition to the animal fables from classical antiquity by Aesop and Phaedrus, he also based his rhymed works on the Panchatantra stories from Indian literature. These ancient works contain many anthropomorphic stories, or stories in which animals have human characteristics.

Particularly well known are The Cricket and the Ant and The Raven and the Fox, which was published in 1668 in his first volume, Fables choisies, mises en vers. The second part was published two years before his death. In their entirety, his oeuvre is an impressive collection of twelve books.

Fables have a didactic purpose, so most contain a moral. The intention is that we learn something from them.

The moral of the Eagle and the Night Owl is stated at the end:

“There someone spoke to her: What is this vain shame?

You owe this disaster to yourself and are to blame,

Of the self-love that drove you,

When you described your children as little angels – it is danger that you drew.

Who had guessed in a thousand years,

That such monsters were the angel statues that so endears?”

Of course, we all think our heroes are eagles. In the end, no one is to blame. Eagle follows his instincts. It doesn’t occur to him that those horribly screeching little monsters could be his friend’s children. After all, they are not even remotely like the beauties described by Owl. Just like Owl wouldn’t recognize that the mice and baby bunnies it catches are the children of loving parents, who do everything they can to protect their young. If it had not been for their friendship and incorrect assumptions, there would have been no problem. Yes, if….

Can we learn from this fable in our own time? What does this story say about the expectations we unconsciously have, for example, with friends from other cultures who may have different expectations? Surely seeing each other for who you really are is a prerequisite for friendship? We can admire each other for the talents we ourselves lack, and for the good character of the other, taking into account that sometimes there are clear differences of opinion.

This raises the question of whether it’s even possible to objectively view our own children, with all of our ingrained presuppositions and prejudices.

The answer is clear: and unfortunately, it’s no. This is a blindspot. The eagle keeps scanning for danger, yet enjoying life as well, like us with the different perspectives of our friends, aware that owls are not eagles. Our perspectives are the products of our origins and our own troubled histories, which we protect and at the same time try to show in the right light.

Miscommunication is lurking. Effective communication requires commitment and even courage. Like coming back to painful mistakes made during conversations. There is even the danger that what you love most will be sacrificed. All the more reason to take up the challenge, based on the understanding that we don’t give up what is dear to us and belongs to us. Does this happen unexpectedly?

Don’t give up hope, but pick up the thread again, untangle it and keep trying.

The moral of this story: sad stories can teach valuable lessons.

[1] Jean de La Fontaine (nagevolgd door J.J.L. ten Kate) – De fabelen van La Fontaine – Amsterdam, Gebroeders Binger, 1875? (1e druk). Geïllustreerd met platen en vignetten door Gustave Doré.