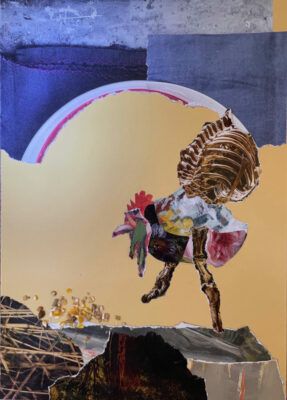

The Rooster and the Stone

Translation into English Greg Suffanti

After a fable from Aesop and De La Fontaine, vijfde boek, fabel XVIII[1]

[1] Jean de La Fontaine (nagevolgd door J.J.L. ten Kate) – De fabelen van La Fontaine – Amsterdam, Gebroeders Binger, 1875? (1e druk). Geïllustreerd met platen en vignetten door Gustave Doré.

Annelie van Steenbergen, text and images.

Anyone who doesn’t like fables is stupid. At least, that is what we can conclude from the very first fable from the first book of the famous Greek fabulist Aesop, told by the narrator Romulus.[1] If you feel addressed, please read on.

Aesop (Esopus, Aisopus) probably lived from about 620 to around 560 BCE. Many of the fables attributed to him are still widely known. Who does not know the story of The Cricket and the Ant or the Raven and the Fox? Phaedrus, who was the first to versify Aesop’s fables into Latin, and an unknown author who wrote the Esopet, greatly contributed to the fables’ popularity.

And of course Jean de La Fontaine (1621-1695), who arranged the fables in rhyme and adapted them to his own time, such as the very first fable, told by Romulus. According to Romulus, he translated the fables from Greek into Latin, and according to him:

Shall they enlighten and sharpen your minds, and give you cause for mirth.

So pay attention!

The first fable is about the Rooster and the precious stone. It is a short fable in which a Rooster is looking for food on a dunghill. While scratching, he comes across a particularly beautiful stone. He salutes the stone and addresses it:

Ah, extraordinarily beautiful, precious stone. You’re lying here in the dung. If someone had found you, who wanted you, he would have gladly praised you and brought you back to your old splendor. But I found you for nothing, and I can’t use you. Therefore, I can mean nothing to you, and you, nothing to me.

End of story.

And as befits a real fable, the author adds a moral. Or in this case, an explanation. The fable is about us who read this fable.

The Rooster represents the stupid person who does not seek wisdom or knowledge. The stupid man is like the Rooster that despises the stone, even though it is precious. The narrator explains once more:

By the precious stone is meant this very book before you: It is beautiful and pleasant.

So suppose you are a venerable person who loves and cares for your neighbours, who does not like fables, thus you are a stupid person. Is your hair standing on end yet? Because, what would you do if you were the Rooster? A stone or a book, after all, a Rooster can’t do anything with either of these? Did he really have a choice? And the key question: Does any of this make the Rooster a fool? An empty head? An ignoramus? And if he is a fool, then the question is whether that is his own fault?

In this case, we’ve come up with a simple answer:

Balthazar Strong Boy de Saint Francois d’Assise, that’s his name. A dignified name, and indeed, a dignified creature. He has excellent qualities and he is a prize winner at the local poultry show. With his high boots with star-shaped spurs, shiny feathers of royal blue and orange, a flowy red hat capping lavish plumage, he is a feast for the eyes. A herald of arms full of splendor, dressed in court costume. He is Lord and master of a productive harem. He strides proudly over his peasant’s land, watching over his wives, and trumpets his message from the housetops. In short, he is quite the chatty and proud Pete.

And the Rooster in the fable is certainly not stupid. After all, he recognizes the Stone as something very special, and he relates to it by addressing it:

Ah, exceedingly beautiful precious stone,

Complimenting the Stone.

Though you lie lost in the dung, I see that your facets can sparkle and twinkle under our God-praised sun. The sun that I greet every morning with my exuberant cooing, that lets everyone know that a new day has arrived, a day to celebrate life. You, Stone, honor the sun in your own way, by reflecting its rays in multiplicity, so that men may become aware of the hidden treasures of the earth.

Even if the Stone does not answer, the Rooster does not give up.

He continues:

“It’s just a shame that you’re lying here in this mess, instead of in a ring on a lady’s finger. With her, you would be appreciated. She would polish and rub you shiny until all the dung residue is gone, and you’d glisten and sparkle in the light, emphasizing her enchanting beauty and do justice to nature.

Unfortunately, the Rooster, no matter how talented and benevolent, can do nothing with the Stone. To him, the Stone is a useless thing. It does reflect the sun’s rays, but he considers his own task as a messenger between heaven and earth to be more important and more comprehensive in scope. He assists the sun by announcing its arrival far and wide with his clamorous crowing.

So, the Rooster concludes that he has found the Stone for nothing:

I can’t use you. Therefore, I can mean nothing to you, and you, nothing to me.

After these considerations, he makes a decision. After all, wouldn’t it be strange if he took the gem to his coop to decorate one of his hens? That’s pretty much the same as keeping a book of fables, however wonderful, unread in a bookcase:

He sighs:

Now I can pass this precious stone in good decency and leave it lying in the mud.

He takes a big step and jumps nimbly from the dung heap. Satisfied, yet with a vague sense of guilt for leaving the Stone to lie there; something out of place here, and probably unhappy in this environment where the Stone is unappreciated and ignored.

What do we think of the Rooster now? Like a fool who doesn’t know what he’s missing? Or as someone who realizes that he has no power to change another’s’ life?

This dilemma has been recognized in later times. Around the middle of the 17th century, Jean de La Fontaine adapted the story to his own time and views in Fable XX, The Rooster and the Pearl.

In the De La Fontaine version, the Rooster helps the Stone escape from its predicament. He rolls the pearl out of the dung heap and takes it to a goldsmith, who is naturally happy with such a precious stone. However, the Rooster informs the goldsmith that he’d much rather have found a grain of wheat, rather than this hard, inedible tuber.[3]

Also in our time, let’s change the moral of the story to a call to reading books of fables and learning from them. We can try to recreate the stories, adapted to our own time, addressing current problems and possible solutions. Just as Jean de La Fontaine has changed the fable by giving Stone a proper destination.

Isn’t that a nice moral to end a story with?

Noten

[1] Het leven en de fabels van Esopus (2016) Teksteditie met inleiding, hertaling en commentaar door Hans Rijns en Willem van Bentum. Hilversum: Verloren.

[2] Het leven en de fabels van Esopus (2016, p. 163)

[3] Jean de La Fontaine (nagevolgd door J.J.L. ten Kate) – De fabelen van La Fontaine – Amsterdam, Gebroeders Binger, 1875? (1e druk). Geïllustreerd met platen en vignetten door Gustave Doré.