Annelie van Steenbergen

text and illustrations [0]

January 2026

‘Traveling to each other’s ‘worlds’ allows us to be together by loving each other’

María Lugones

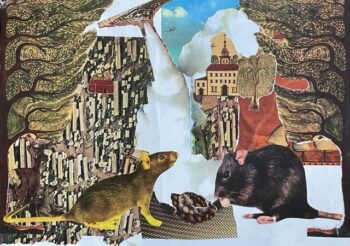

Two Rats

Sometimes a quote on a tear-off calendar prompts us to reflect a bit more on a particular topic. ‘Traveling to each other’s “worlds” allows us to be together by loving each other’ is an example of this. This quote from the Argentine feminist philosopher María Lugones [1] (1944-2020) refers to an article in which she introduces the concept of ‘world-traveling’ as a possibility, or rather a necessity, to understand and experience the diversity within and between cultures, races, sexes, and religions, and thereby to love. ‘By inhabiting different overlapping “worlds” and speaking multiple “languages,” we gain access to different perspectives,’ states the back of the calendar page. Those who do not speak the other’s ‘language’ well enough can be excluded or retreat into their own bubble, but according to Lugones, not every word needs to be translated. Ambiguity can remain. ‘By embracing the other as multifaceted, we can strive for a more inclusive society.’ In Lugones, it is primarily about women, the coloniality of gender. The question is whether we might also apply this to the gap between rich and poor or between rural and urban areas. Animal fables are often a suitable playground for philosophizing about such human variations.

The freedom of the poor rat, according to Aesopus

One such fable, which has been adapted and retold throughout the ages, is the fable about two rats by the famous Greek storyteller Aesop [2] (620-500 B.C.). In this fable, besides the division between town and countryside, there is also the contrast between rich and poor. It is about a well-fed fat rat, who resides in the cellar of a wealthy man, and a thin wretch, who, according to Aesop, looks pitiable and lives in a small burrow out in the field. It is clear that here the wealthy individual is set against the poor fellow, and the introduction of the story already shows who has the more favorable position. According to both Aesop and the rat who lives in simplicity, it is far better and more pleasant to live in poverty and be free than to live in wealth and have worries. In the fable, this statement is illustrated through an encounter between the two.

‘One day, the fat, chubby rat went to relax in the field, and while she was there, she came across another rat on her way, who was thin and pitiful.’

She welcomes her hospitably despite her poverty and treats the other, who usually lacks nothing and now after the walk is quite hungry, to fruits and grains from her modest supply and gives her a drink from her little water. After they have eaten and drunk, the fat rat invites her new friend for a return visit:

‘Come with me and I will give you very different food.’

Together they go to the city and arrive in the living cellar of the fat rat, where an abundance of delicacies is kept. A paradise of everything you can imagine. You can imagine that the thin rat doesn’t know what she is seeing, and when the fat rat offers her the expensive food and says, ‘Be cheerful and eat and drink with pleasure,’ she doesn’t need to be told twice. Then, while they are indulging in the most delicious foods and drinks, the cellar master comes down the stairs.

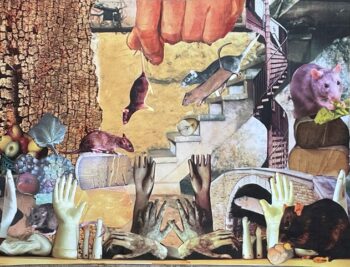

‘The fat rat immediately ran to her little den, where she always hid. The other, poor rat didn’t know where to flee, but hid with fear and trembling behind the door.’

The cellarmaster rummages through the food for something that suits him, and he has not even left before the fat rat appears again. She calls out to her trembling friend not to be afraid and to eat as many treats as she wants. The poor rat does not dare, she has already seen enough. In every corner, behind every grape, behind every cheese, she fears danger. She begs her host to help her get away from here,

‘because I would rather eat grass and grains and live in freedom than always be afraid and, furthermore, be sad. For you are in great danger here and live in uncertainty.’

Then Aesopus concludes in the same manner as he began:

‘That is why it is a cheerful thing to live in poverty and be free, for the poor man lives in security and in greater freedom than the rich.’

Hapiness of the Town Rat and the Country Rat

This fable has many variants. For example, Jean De La Fontaine [3] , who rewrote many fables in the seventeenth century and put them into rhyme, leaves it open in The Town Rat and the Country Rat how the two such different little animals have met. Also, the striking distinction in Aesop between fat and lean, between rich and poor, is not mentioned here. His poem begins as follows:

‘Surely a town rat

Urged a country rat to try

A bit of a dove,

With a slice of ham or something.’

The story in this case takes place in the elegant dining room of a wealthy family. On the table, which is covered with a Smyrna carpet, are the remnants of an abundant meal. They have just started feasting when they are disturbed by sounds from outside the door. The city rat dashes away, and the field rat, trembling all over, follows him as best as he can. When the hall becomes quiet again, they sneak out of their hiding place. The city rat tries to convince his friend to resume the meal. However, the field rat cannot be persuaded. Unlike the edition by Aesopus, here the field rat invites the city rat to visit him in return at his home in the peaceful countryside:

‘The bites

May not be

Of a princely kind, like here:

But no one attacks me.

Good evening! No pleasures

Can be savored,

Spoiled by constant fear!’

A clear moral lesson is missing. The teaching that being poor in the countryside is preferable to being well-off in the city has been replaced by the personal preferences of the rats: the city rat simply loves hustle and bustle and a good meal, while the country rat prefers peace and safety.

A contemporary remark on De La Fontaine’s retelling

There is, however, a caveat to this. Nowadays, it is not always a pleasure for a field rat to live outside. The dangers are of a different kind, but they certainly exist. Even in open environments, rats have many enemies. Martens, dogs, cats, and birds of prey enjoy hunting these little creatures. And just like pet chickens, they eat worms, drink rainwater, and forage on the ground, which can lead to the intake of harmful PFAS. Moreover, surface water is often heavily polluted, resulting in infectious diseases. In contrast, rats in the city live not only in the sewers but also in basements or attics, nice and warm, dry, and out of the wind. The dangers faced by the city rat are somewhat exaggerated by the field rat. It is reminiscent of the current controversy between city and countryside residents.

Recent research by the Social and Cultural Planning Office (in the Netherlands)[4] shows that the supposed gap between city and countryside is smaller than you would expect from the above myths. Structural inequality in our country is less related to place of residence than to social differences that stem from a lack of resources such as a social network, income and financial assets, or good health. ‘The differences within areas are always greater than the differences between those areas,’ the report states. According to the researchers, the emphasis on the so-called gap between city and countryside is dangerous because ‘the more we act as if the gap exists, the more it becomes a reality.’ It can lead to adversarial thinking, distrust, and tensions: the more we see and emphasize the differences, the more they come to life. The researchers point out that there are significant inequalities in life opportunities and in feelings about the state of society and politics, even within towns and regions. So, also within the cities.

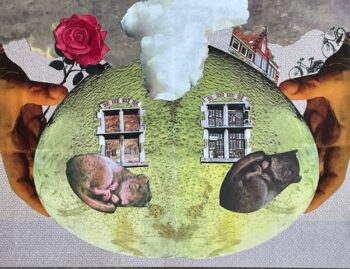

Contemporary cosmopolitan life in the city and in the field

And so we return to philosopher Maria Lugones and her overlapping ‘worlds.’ Clarifying this is the adaptation of the fable of the two rats in our own time. In the contemporary classic ‘City Mouse and Country Mouse’ by Kathrin Schärer[5] , instead of the little-loved, let’s say hated, rats, two adorable little mice take the lead. In this beautifully illustrated children’s book, the contrast between rich and poor, city and countryside, is bridged through the meeting and exchange based on equality.

In short, it comes down to this: City mouse goes to visit Country mouse. He is frightened by everything Country mouse introduces him to. The gigantic cows, the stench in the pigsty, the aggressive rooster, the prickly stubble in the wheat field… Yet he also stands full of admiration, hand in hand with his little girlfriend, enjoying the sparkling night sky, and he really enjoys the simple meal of nuts and berries in her cozy home. Snuggled up against each other, they then fall asleep. The next morning, at the crack of dawn, Country mouse takes him to watch the sunrise.

‘”Oh, how wonderful!” sighed City Mouse. ‘It’s beautiful here with you.

And so different! With you, the sun rises out of the ground.

With us, it comes up behind the apartment building!

Come with me, and I’ll show you where I live.’

It’s easy to guess that Field Mouse feels just as out of place in the big city as City Mouse feels in the countryside. People everywhere, stench, noise, everything seems to have wheels, and food scraps are lying around on the streets. In the supermarket, she becomes nauseous from the bright lights and the noise and eats so much that she becomes sick. When a frightening encounter with a dog becomes too much, City Mouse quickly takes her through the atmospherically lit streets to his sleeping place by the river. There he lives with a horde of other mice. Field Mouse is warmly welcomed by everyone, and they celebrate late into the night. Early in the morning, City Mouse takes her to the quay to watch the first boats slowly chugging under the bridge, surrounded by veils of mist.

‘’Oh, how beautiful!’ sighed Field Mouse. She shivered a little. ‘It’s nice here with you. But now I want to go back home, to my warm little nest in the hay. Because your life is here and my life is there. And your life is beautiful for you, but my life is beautiful for me.’ Then they gave each other a big hug.

The book ends with the promise to visit each other again soon. At the farewell, she turns around a good ten times to wave. And City Mouse waves back.

A wise life lesson: love reveals plurality!

This is a hopeful ending. Traveling to each other’s ‘worlds’ allows us to co-exist by loving each other, Lugones states. For Lugones, love is not seen as merging and erasing differences. On the contrary, it is precisely incompatible with that. Love reveals plurality.

Those who open themselves up to the world of the other and try to understand how others see themselves and us in their world can learn to appreciate the other and form friendships, without imposing their own views and ways of life or considering them better or higher, preferable to those of the other. According to Lugones, ‘we can feel at ease in different worlds by speaking the language of that world, being subjectively happy there, forming personal relationships, and sharing common interests.’

However, feeling at ease is not enough to understand each other: for that, ‘playfulness’ is needed, says Lugones. That is to say, an open attitude that makes it possible to create and accept new ideas without rules or barriers. For the two mice, also known as two rats, it is therefore possible to inhabit each other’s worlds with an open mind, in friendship and love, without having to give up their own identity.

In this way, such an apparently simple animal fable invites you to examine your own life and ask yourself whose languages you can learn and in whose worlds you would like to and are allowed to enter. The wide world of fables is a good place to start the cosmopolis.

Notes

[0] with thanks to Harald Vlugt for the use of his archive.

[1] María Lugones in “Playfulness, ‘World’-Travelling, and Loving Perception”, Filosofie Scheurkalender 2025, maandag 20 oktober. Uitg. Filosofie Magazine, Nijmegen.

[2] Het leven en de fabels van Esopus. Teksteditie met inleiding, hertaling en commentaar door Hans Rijns en Willem van Bentum. Hilversum, Verloren, 2016, p. 175.

[3] Jean de La Fontaine (nagevolgd door J.J.L. ten Kate) – De fabelen van La Fontaine – Amsterdam, Gebroeders Binger, 1875 (?) (1e druk). Geïllustreerd met platen en vignetten door Gustave Doré. Fabel IX, eerste boek, pp. 27-29.

[4] Op 31 december 2025 geraadpleegd van https://www.scp.nl/actueel/nieuws/2025/06/05/ongelijkheid-zit-in-je-sociale-klasse-niet-in-je-woonplaats

[5] Schärer, K. (2009). Stadsmuis en Veldmuis. (vertaling L.M. Niskos). Rotterdam: Lemniscaat. oorspronkelijke titel: Die Stadtmaus und die Landmaus.